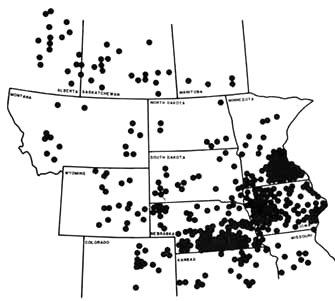

Mammoths were large Elephant-like mammals (Proboscidians) that

evolved in Africa, but subsequently roamed much of the northern hemisphere

during the later part of the Cenozoic Period. Mammoth remains (mostly

teeth) can be found throughout the midwest. Nebraska, Iowa, and Minnesota

have the highest abundance Mammoth-finds. The partial skull, jaw, and

rib of the Brookings County Columbian Mammoth (Mammuthus

columbi ) make this Mammoth-find one of the most interesting

in the eastern portion of South Dakota.

and indicate locations where Mammoth remains have been found. Four species of Mammoth are included on

these maps: M. meridionalis, M. columbi, M. primigenius, and M. exilis. The painting of Mammuthus columbi

by Mark Marcuson is used with permission of the University of Nebraska State Museum.

Visit the University of Nebraska State Museum.

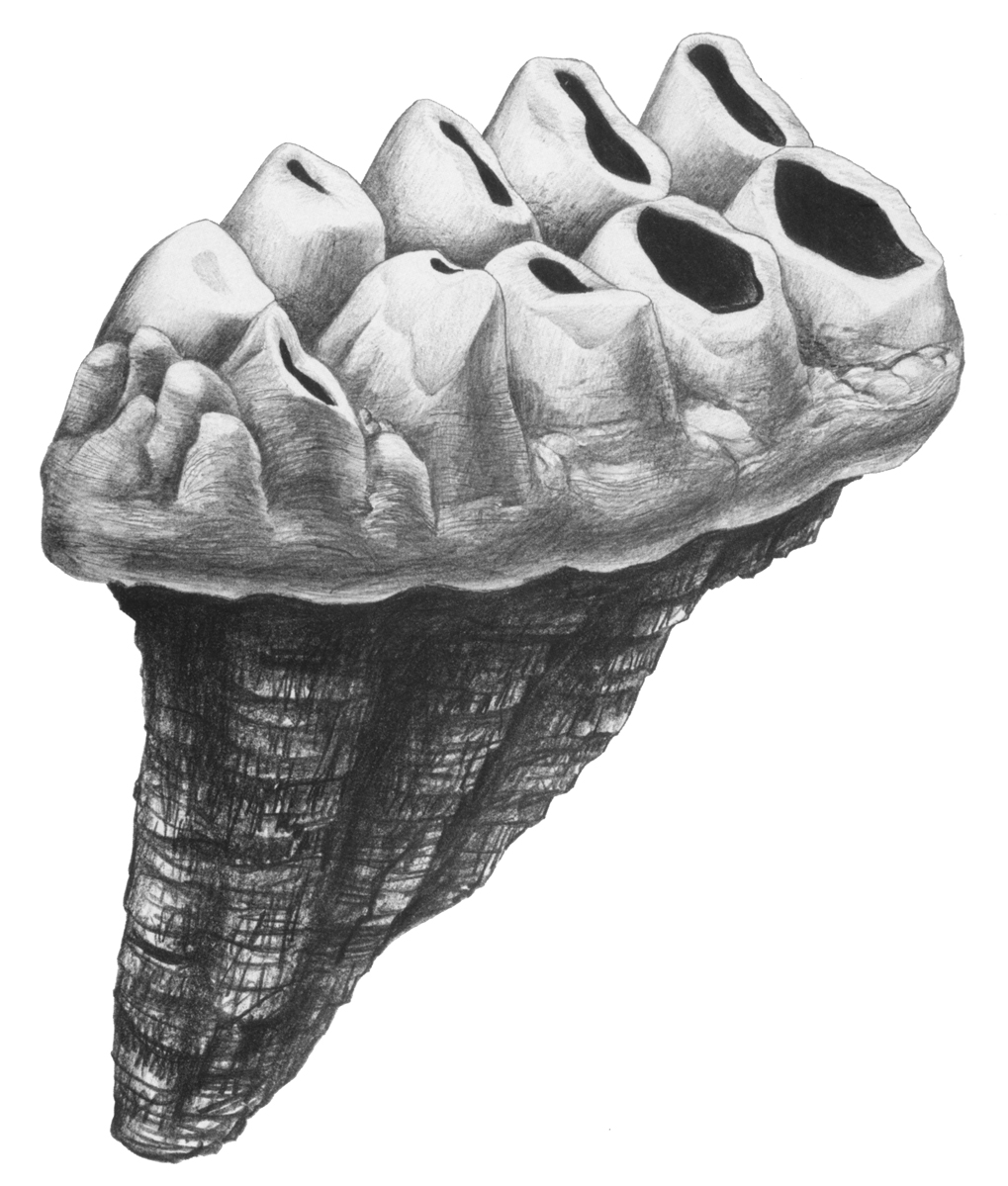

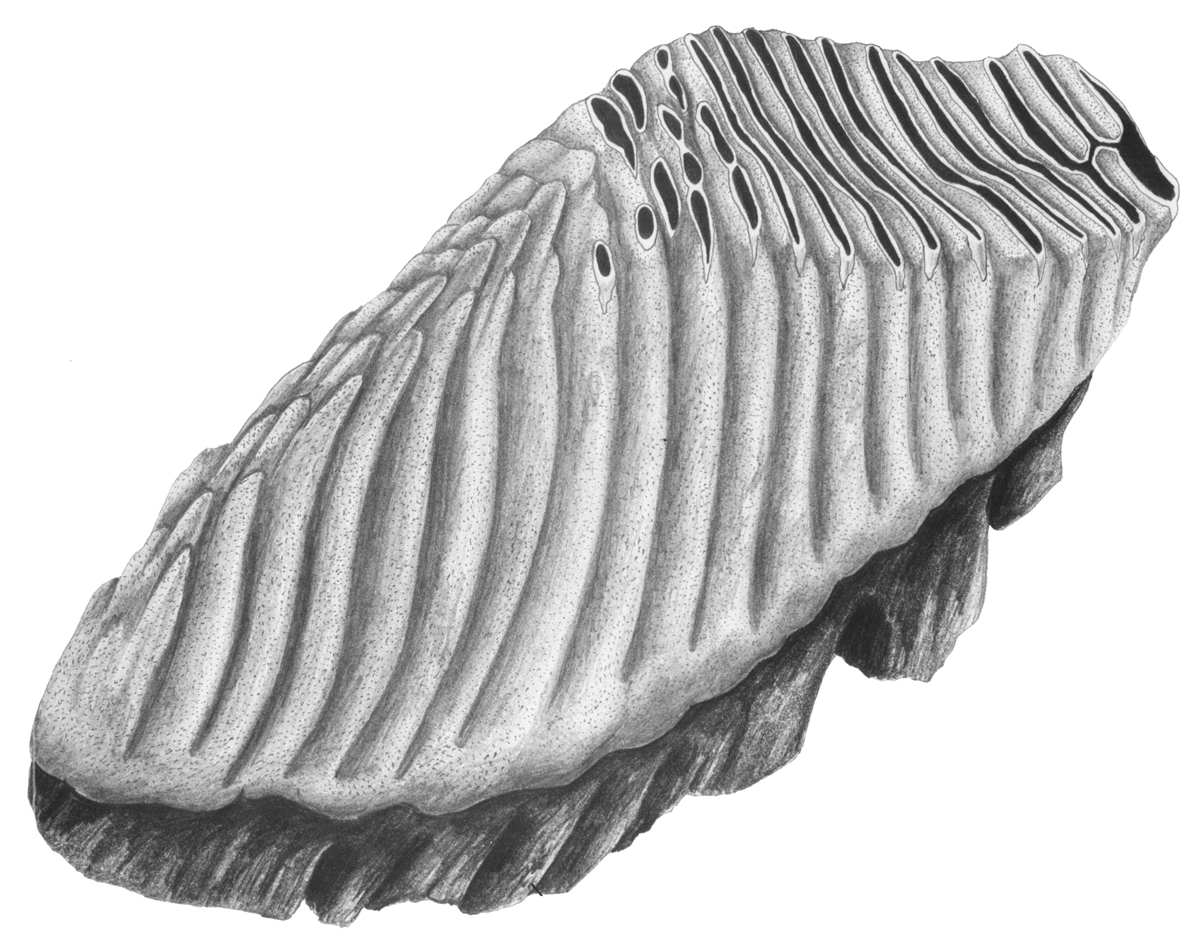

During their lifetimes, Mammoths will have 24 teeth, and these were very large teeth at that. Each tooth (molar) is a series of dentin-filled enamel tubes that take on a flattened, oval appearance as they are compressed into a large blocky mass composed of many such "lophs'. The resulting grinding surfaces of a Mammoth tooth resemble a washboard which makes it quite easy to distinguish their teeth from those of their close relatives - the Mastodons (see picture below).

Mammoth's highly specialized teeth

exhibit a remarkable mechanism by which they grow and are replaced in

succession such that only a single tooth (or a single tooth and a fragment

of another) is present and functional in each quadrant of the jaws at

any one time. In sequence, the front-most tooth is gradually worn away

and replaced by the next in line, and so on. Once the last tooth (6th

in the series) is lost, the animal is in trouble. Fortunately, this conveyor-belt-like

series of events provides Mammoths and Elephants with a functional set

of teeth for up to 70 years. The

tusks are enlarged incisors that also grow continuously throughout the

animals life. Instead of a hard outer covering of enamel, Mammoth tusks

are composed of the slightly softer material, dentin. The longest tusk

on record is from a Columbian Mammoth tusk found in Texas which measures

16 feet long and weighs over 200 pounds.

Drawings are from UNSM Museum Notes #77, and used

with permission of the UNSM. (Mastodon left, Mammoth right:

Artist: M. Marcuson). Photograph is of the lower

right Molar from the Brookings Co. Mammoth.

Photos by Ron Foster, Bill Huser, and Art Huser

On Sunday, Aug. 5, 2001, Bill Huser, and Ron and Jason Foster decided to canoe the Big Sioux River and put the canoe in the River about a mile south of Esteline, SD and headed south to Bruce, SD. Forty-five minutes into the trip they came to a high bank on the west side of the river when Bill said, "Maybe we can find a buffalo skull". Within a minute or so Ron shouted, "There a pair of boots". They weren't boots -- they were the partial skull and teeth of a Columbian Mammoth. Bill contacted a couple of Universities to try and stir up some interest. Dr. Scott Pedersen (SDSU, Assistant Professor in the Biology Department) jumped at the chance to be involved with the project.

Friday Aug. 24, 2001: Bill easily relocated the site located 7 miles north of Bruce and 2 miles south of Esteline, SD [UTM: 4932216E / 0667786N]. The skull was 42 ft from the center of the county road, embedded in a collapsing river bank just above the water level. The bank had clearly been damaged the previous winter by erosion and ice-scouring and was at risk for further bank collapse. Numerous calls were made to the County Commission, the County Highway Department, and to the County Zoning Commission to determine who actually could lay claim to this Mammoth Skull. To make a very long story short (and after reviewing records in the Court House), each Office that we had contacted gave our Team the go-ahead on the project. As it turns out, the County has 'control' over all things within a 100' buffer zone (50' to either side of the centerline) along the road in question. The head was 42' from center of the road and belonged to the County. We were also in contact with Dr. Miles Gilbert of the South Dakota State Historical Society (Rapid City) who wanted to visit the site before the Team got under way with our excavation. Dr. Gilberts' interest was to see if there was any evidence (e.g., arrow heads, stone tools) that would indicate that this Mammoth had been killed and butchered by paleo-indians and therefore be an important archaeological site for South Dakota.

August 30th, Drs. Gilbert and Pedersen dug an exploratory trench and sifted through several cubic yards of soil These efforts indicated that we only had the partial skull of a Mammoth. We found no evidence of the rest of the animal, nor did we find any evidence of paleo-human involvement with the site.

August 31st: Serious excavation began at the site. During their initial efforts, Bill came across the entire jaw bone of the Mammoth submerged in the shallow muddy waters along the river bank. The jaw had the appearance of drift wood and was covered with moss, but Bill quickly realized what he had quite literally stumbled across. Further surveys by Bill and Ron located many more pieces of bone near the waterline just upstream from the skull. Friday afternoon was a very exciting time for the novice fossil hunters! Throughout the afternoon, using shovels, trowels, a home-made sifter, the Team greatly expanded the trench made that morning by Gilbert and Pedersen, and sifted through all of the excavated material. No further evidence of an intact animal could be found (i.e., vertebrae, tusks, and long bones). As the day ended, they began to think of how on earth they would get this extremely fragile 250-350 pound mammoth skull along an eroded 300' "trail", then up a 20' river bank, and finally into protective winter storage at SDSU.

Saturday, September 1st: The first step was to stabilize the exposed stump of the shattered left tusk. We diluted Duco-Cement with Acetone and produced a shellac-like mixture that penetrated and consolidated the tooth fragments into more-or-less solid mass. After having dug a complete trench around the exposed skull, the Team decided that the best approach would be to the standard technique of constructing a 'Plaster of Paris' jacket around the skull to secure it during transport. The second step was to drape the skull in damp toilet paper which would serve as a separating-layer when we eventually remove the skull from its jacket. Burlap strips were then dipped into the 'Plaster of Paris' and wrapped around the skull in numerous over-lapping layers. Several strips of wood were also plastered into place to offer further stability. This process took several hours during which the greatest problem was keeping the underlying sand moist so that it would not crumble away thereby toppling our jacketed-skull before we were ready to flip it over onto its top for transportation.

When we had found the skull, the braincase and forehead were already badly fragmented and/or missing. The day was hot, the sand dried out, and the massive skull shifted. Many of the very small bone fragments (< 1") were lost or further separated from the rest of the skull. All of the fragments were saved but most of them were too small to have even attempted their reconstruction in the first place. Towards the end of the day, the Team was covered in plaster, and the skull had taken on a rather unattractive 'lump-of-plaster' appearance. At this point in time, the Team began wonder how they were going to move this heavy, unbalanced mass and brainstormed over several innovative plans. It was decided that we would carry it! Scott and Bill widened the river bank with a pick-ax in order to give the Team a stable walking surface. We let the plaster to dry overnight in the cool evening air, and retired to our dinners and bed.

September 2nd: We met at about 9:30 am and found that we had a new Team member, Brian Lester from Sioux City. We pooled our resources and decided to sling the skull beneath a wooden beam that we would carry upon our shoulders. After a bit of creative rope-tying and a chorus of rude grunting noises, four men (Bill, Scott, Brian, and Ron) carried the skull 300' to the end of the river bank and then slung the skull onto an aluminum ladder that rested against the embankment. The ladder would act as a sledge that would be towed up the bank to the shoulder of Brookings County Highway #7 by Ron's truck. It worked beautifully. The ladder was then muscled into Pedersen's truck for the drive into SDSU. Once at SDSU, we hoisted the skull onto a cart and finally set it to rest on a pallet near Pedersens' research laboratory. The jaw (mandible) did not require as much effort and did not need to be plastered. It was kept separate from the skull and is presently stored in Pedersen's Research Lab. For many members of the Team, it was quite difficult leaving the building and 'their' skull behind. After all that time spent with the skull, and after all the effort that had been expended, they had become rather attached to it.

On Monday Spetember 3 (Labor Day), several people returned to the site and dug further test trenches in an effort to located new material. Within minutes, Art Huser noticed many bone fragments in a shovel full of dirt, 8' downstream from the original site. Art began to dig more carefully and uncovered a 30-inch long segment of rib. A few other small fragments of bone were located where the jaw had been fished from the river, but little else was found on this day.

2001: L>R = Scott Pedersen, Ron Foster, Brian Lester, Art Huser, & Bill Huser

Personal note from Ron Foster (2001) : As the time to go home came near, the ones who dug all realized that we had truly experienced a once in a life time moment. A proud feeling came over me. That I had met something in the past and it was meeting the future after a long time. Now it can be used for others to study. This might help people to realize what the past was like. I have taught for 29 years this year. And I have taught about this mammoth. But it was only in textbooks. Now I know how others feel when they find something special like, our mammoth. It was very exciting and great pleasure to help recovery the past for our children to learn from. Bill and I wanted to name this fossil "Sioux II" because Sioux River, Sioux City and the original Sue fossil out near Rapid City. [rfoster46@aol.com]

Digging

Renewed After Two Years' Absence

September 2003 - by Ron Foster

The last week of July of 2003, I received an email from Mike Fosha from the State Archaeology Department stating they wanted to do a dig at our mammoth site on the Big Sioux River. It just about floored me. After all this time, nearly two full years, someone with the expertise wants us to unlock some more pieces of our puzzle. I was so excited that I contacted all who was part of the first discovery. Everyone began making plans on to come during the weekend of Sept 5-7th.

I met Art Huser at our Cabin on Thursday Night. We arrived at the site early on Friday Morning, September 5, with my collection of pictures, figures and digging tools from the original dig. There at the bend of the river was a group of about 12 excavators working already, but most were working too far down stream. Only 2 test plots were dug even near the correct place. I introduced myself to Mike Fosha, assistant state archaeologist, and asked why most of the people were digging in the wrong area. He said, “When we started on Thursday, the landowner directed to this area and said, the mammoth was found there.” That was about 300 yards downstream from the first excavation. After showing much of his group the pictures and identifying the original site, they began in earnest to uncover the past. Within an hour or so Harlan Olson found a large piece of pelvic bone in the river using a pitchfork to feel with. I was so excited that I ran down to look and I carried the bone up the embankment to give it to Mike on the top of the bank. It must have weighed 40 lbs.

We worked all day. Most of the people in Mike’s group are a collection of volunteers who stay in touch with Fosha. This group was from various places such as, Minneapolis, Arizona and from all over South Dakota. Mike sends out an email and they come running to help and to learn from him I vicariously became part of their pervious digs after listening to the stories about what they have found. On Friday, we laid the ground work for the weekend. We did find much in terms of pieces of bones but moved tons of dirt.

On

Saturday, Jason Foster, Bill Huser joined in on the dig. Now all the original

finders have come back to dig some more. We headed out to the site and

each chose a place along the bank to dig. It was slow going; Mike wanted

us to sift each mm of dirt through the cultural layer of dirt. This layer

was a very dark layer of dirt which could have supported abundant live.

We had to look at it carefully for its archaeology value. This layer was

much higher than the original level of the mammoth layer. We worked all

day Saturday and into Sunday, removing this layer finding a few points

or piece of points. These were the remains that early man left when making

spear tips or other items. These pieces are very small and hard to find.

On Sunday, I left to site about 2 o’clock. His team of diggers was slowly leaving, too. Bill Huser and Scott Pedersen talked with Mike about moving down to the original layer where the mammoth skull was removed. The rest of the day, the group moved tons of dirt to reach the original layer. As the day’s ends, most the volunteers have left the site to go home. Mike returns on Monday and writes to me, “Things got pretty exiting on Monday. It is then we found the point performs (looks like Agate Basin) but it could just be a biface from any Paleo-Indian time period) a basin and what looked like a stone filled pit. Upon coring the pit we got mammoth bone. I am going to try to get a blurb written up for this Newsletter.” This was exciting news. I asked Mike to send me copy of the Newsletter.

Read

the Newsletter Article!

(.PDF format)

South Dakota Archaeological Society, Vol. 33,

June 2003

About a month later, Mike states, “I received the radiocarbon date back today. It is pretty exciting. The Conventional Radiocarbon age is 10,910 +/- 40 BP. The 2 Sigma Calibrated results are Cal BC 11,180-10,890 (Cal BP 13,130 to 12,840). These certainly fit the later part of the Clovis period which is exactly what I thought we might be dealing with although there still might be two components.” Mike stated, “This is really exciting and we have some specialist who will help work on the site next fall/late summer. Just think, another dig, possibly next summer. Our site is becoming more interesting to both experts and amateurs alike. I know that I understand very little of what the specialist will be looking for. But I do understand, this discovery is very important in understanding that Mammoth and early man did meet.

The

2004 field season at the Mammoth dig-site/locality near Estelline (Brookings

Co.) yielded several new finds including bones and stone tools. The dig

site cuts through multiple buried soils which provide archaeologists with

paleo-environmental data and the relative age of the deposits. In this

case, the soil level that Mike Foshas’ team have concentrated on

during the past two years is a black soil known as the Leonard Paleosol

which began forming as early as 11800 years BP.

Mike Fosha and the 2004 team detected at least two, and possibly three,

cultural components at the site - the uppermost component is near the

top of the Leonard soil with a carbon-14 AMS date of 9010 ± 60

years BP. Approximately 10 cm below the upper contact of this soil (where

a possible Agate Basin point preform [ca. 10300 - 10100 BP] and bison

bone were collected in 2003) additional flakes were recovered consisting

primarily of Knife River flint from North Dakota quarries.

Cultural material consisted of bison bone associated with a small number

of chert flakes in the paleosol. To date, no Rancholabrean fauna other

than bison have been recovered in the Leonard paleosol and this location

is no exception. Numerous re-sharpening flakes, one butchering tool, numerous

pieces of charcoal, and one piece of mammoth bone was recovered below

the Leonard paleosol in a dark-brown silty-clay above sands which overlay

large cobbles/boulders that underlie the site assumed to be glacial outwash.

The mammoth bone is a small section of a leg bone with spiral fractures

that are consistent with breaking the bone while it was still green (possibly

a young animal). An additional carbon-14 AMS date of 10,860 ± 40

years BP was recovered from this soil contact approximately 10 cm lower

that the 10,900 ± 40 date obtained from the 2003 investigations,

i.e., it is statistically equivalent to the previous date and date the

site to the “Clovis Age”.

Next years’ investigation (2005) will focus on completing some of

the test units that were not finished this year and to expand the excavation

to the north and south to determine the size of the site and hopefully,

to find a Clovis or other diagnostic spear-point in association with some

mammoth bone or mammoth bone tools.

At the final posting of this web-site (November 1, 2004), ALL mamoth remains have been transferred to Mike Fosha for study and publication.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Earthwatch: Hot Springs South Dakota Dig site

South Dakota State Historical Society

South Dakota School of Mines & Technology: Museum of Geology

Ashfall Fossil Beds State Historical Park

Contact Information:

If you have any questions

concerning the content of this web-page

or would like to supply further links and info, please contact:

Scott C. Pedersen, Ph.D., Dept. Biology & Microbiology

South Dakota State University, Brookings, SD 57007-0595

TEL-605-688-5529, FAX-6677 Scott_Pedersen@SDSTATE.edu

![]()

![]() Report all dead links/images to Scott_Pedersen@SDSTATE.edu

Report all dead links/images to Scott_Pedersen@SDSTATE.edu